Meet Me By the Fountain: Talking Malls with Alexandra Lange

Let's get into the history of malls, some favorite pop culture representations, and the future of mall culture.

This is a free post for subscribers of Landline, a pop culture and history newsletter for people who care about the Titanic, and the the Kate Winslet vehicle of the same name. Consider subscribing to the paid plan to get my weekly email of recommendations and links, a podcast episode, and more! You can also help me spread the word by sharing it with a friend who would love it.

In the past week, I’ve been seeing a lot of mall-related news, whether it’s the recent news that Macy’s will be closing 150 of its stores nationwide—how will malls repurpose those spaces? Hockey rinks? (Never forget Tanya Harding trained at a mall)—or, making me feel older than I am, news that mall retailers of my youth (GAP, Abercrombie & Fitch, etc.) are making a comeback. Or, just the sobering headline “Mall security guard reportedly fired for doing ‘doughnuts’ in parking lot while playing ‘Not Like Us.’” (An icon.)

I’m so glad I got the chance to interview Alexandra Lange, design critic, and author of a book I absolutely love, Meet Me By the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall. We talked about the history of malls, some favorite pop culture representations, and the future of mall culture.

I’m curious about what inspired your foray into malls. Had malls been important spaces to you growing up?

My family moved to Durham, North Carolina in the early 1980s so yes, malls were very important to me as a teenager. I spent a lot of time at Northgate and South Square (both RIP), shopping at the Gap and the Limited, getting my ears pierced at Piercing Pagoda, checking out YA and romances at Waldenbooks. When I started thinking about writing a book about architecture that was meaningful, popular and powerful, malls immediately came to mind.

Can you share a bit about how we get malls in the US? When and where were the first big malls built?

The Father of the Shopping Mall was an architect named Victor Gruen, a Viennese emigre who fled the Nazis and came to New York in 1938. In his early career he designed extremely stylish boutiques, then he moved on to freestanding department stores, so he had a front-row seat for the ways the postwar expansion of the suburbs was disrupting traditional, downtown-focused models of commerce. He designed the first indoor shopping mall, Southdale in Edina, Minnesota, which opened in 1956. The second, developed by another mall pioneer named James Rouse, opened outside Baltimore later that year.

Imagining malls emerge from department stores as previously existing large retail spaces, how did they build on this previous form? What do they offer that’s “new?”

In many ways the mall is an exploded version of the department store. Most major US cities had a large, historic, family-owned department store that anchored its downtown shopping area – Wanamaker’s, Hudson’s, Kaufmann’s, the original Neiman Marcus, Dayton’s – and those stores had central atriums with fountains and plants, restaurants to extend the shopping day, ladies’ lounges and bathrooms, all the things that make malls convenient places to shop. Their innovation was in expanding the walkable, “public” space between the department stores, boutiques, and services, and giving suburban-dwellers a place to walk around, let kids blow off steam, meet their friends, in any type of weather.

I didn’t know until reading your book that food courts only date back to the 1970s. Do you think they helped contribute to the mall as a social space (particularly for teens)? Do you think they are a value-add for malls more than the lunch counters that came before in places like department stores?

I was surprised to find this out too! 1974, Paramus Park Mall in New Jersey was the first food court. I think food courts are incredibly important in extending people’s stamina for shopping, supporting hang-out culture, and further reducing the cost of being out. You can literally hang out there all day for nothing – or the price of an over-iced soda. Department store restaurants have always been geared toward their middle-class woman shopper, in decor and menu, and while Woolworth’s lunch counters existed at a lot of malls, by the 1970s those were in decline. Having inexpensive food, and the ability to gather at a table, really supports the social dynamics of the mall and of teen culture.

What is your go-to food court recommendation?

Auntie Anne’s! Just plain, no cinnamon sugar or dipping sauce.

I was really interested to learn about the Gruen transfer, just part of the legacy of mall architect Victor Gruen. To me, the “Gruen Transfer” feels like my modern-day “Target problem,” or the idea that I go to Target with a list of things I need and quickly forget why I’m there and buy all kinds of things I don’t. I’m wondering if you think the Gruen transfer is still place-based, or if its greatest legacy is online in e-commerce design, social media sales, TikTok sho, etc.?

Your Target problem is definitely the Gruen transfer at work, and I think it can come upon us anytime, anywhere in a big store with lots of visual enticements. I often get that way in big outdoor stores. Like, I’m at L.L. Bean and suddenly I’m considering different sizes of carabiners. I think it is still place-based, but I also think the infinite scroll on a platform like Instagram, where I follow a lot of brands, can be very, very similar. I put a lot of things in carts but thankfully, I am aware enough not to buy (most) of them.

Malls have never been public spaces, but consumers think they are. Do they have a role as public space?

Malls have always had a role as “public” space. Victor Gruen’s original concept for the mall was as a gathering place, akin to a town square or village piazza, in the new suburbs which had made no provision for community gatherings. Whatever light you view postwar suburban development in, living there would have been a demonstrably worse experience for women and children without a pedestrian-oriented place to meet, shop, and eat together. Early malls often had spaces set aside for community gatherings, and many even included nurseries where you could drop a child off while you shopped. The dominance of cars in the built environment has only increased over time; people still need safe, climate-controlled, low-cost places to gather that are close to their homes.

Malls as originally conceived were ideally a place for community gathering and commerce and became a location designed to appeal to white-suburban women. Do you see conversations nostalgizing malls as having anything to say in the rising discourse about trad-wives online? Specifically, there is such nostalgia for malls as they were 30-40 years ago. Does mall nostalgia and trad-wife trade in a strange nostalgia for a perceived loss of power/influence for consumers, white women, lost traditions, etc?

This is such an interesting question, I would never have thought to put these two discussions together but I can see it! That said, I think tradwife nostalgia and mall nostalgia are different in a couple of ways.

First of all, tradwife nostalgia is for a pre-technologized time in the American home. They make a big deal out of doing things by hand, and often reject healthy advances in technology (like milk pasteurization! Which was a huge pro-child health campaign in the 1920s), along with rejecting fashions of the 20th and 21st century (j/k). If mall nostalgia centered on the 1960s and those white, middle-class housewives a la Betty Draper, it would be a lot more consumer product-driven! Vacuums not handmade brooms, the magic of TV dinners rather than sourdough starter, etc. etc. One of the ironies of tradwife influencing is how their presentation of a kinder, gentler, no-phones-visible time is only made possible by lots of phones and cameras, and the money they make is generally by pushing products.

Second, mall nostalgia’s actual center is on teen experience in the 1990s. That experience is also white-coded: as I write in the book, most of the famous teens-at-the-mall movies are focused on white female teens, and Black media depictions of teens-at-the-mall tend to be more mixed, and involve encounters with mall cops. But, in both cases, the teens want to go back to the mall! It’s a place where, in the best case scenario, they can be themselves and have a little bit of freedom from the adult gaze. The nostalgia is for hanging out in person and it doesn’t have the same proscribed roles in terms of race and gender as tradwife culture.

I really loved your writing on cultural interpretations of malls, particularly your insight that the library in the Breakfast Club was inspired by a mall. When malls show up in pop culture, what work do you see them doing, and has that changed over time?

If you see a mall in a movie, two characters are about to unexpectedly run into each other, drama will ensue. That’s it, that’s the work. That hasn’t changed over time but I bet it is much more difficult for screenwriters to find places for people to unexpectedly run into each other now.

Can you share a favorite example of a mall in pop culture?

All those teen singer mall tours. I was a teen when Tiffany, Debbie Gibson, Alanis were doing those tours, so I didn’t really understand their context: when neither the singer nor her fans is old enough for the club, and the Swiftie Dad has yet to appear on the horizon, how do you get your songs to the people? The mall.

I also want to point out a more contemporary piece of teen pop culture that feels like it should have a scene in a mall, but doesn’t: To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before. That diner could have been a food court.

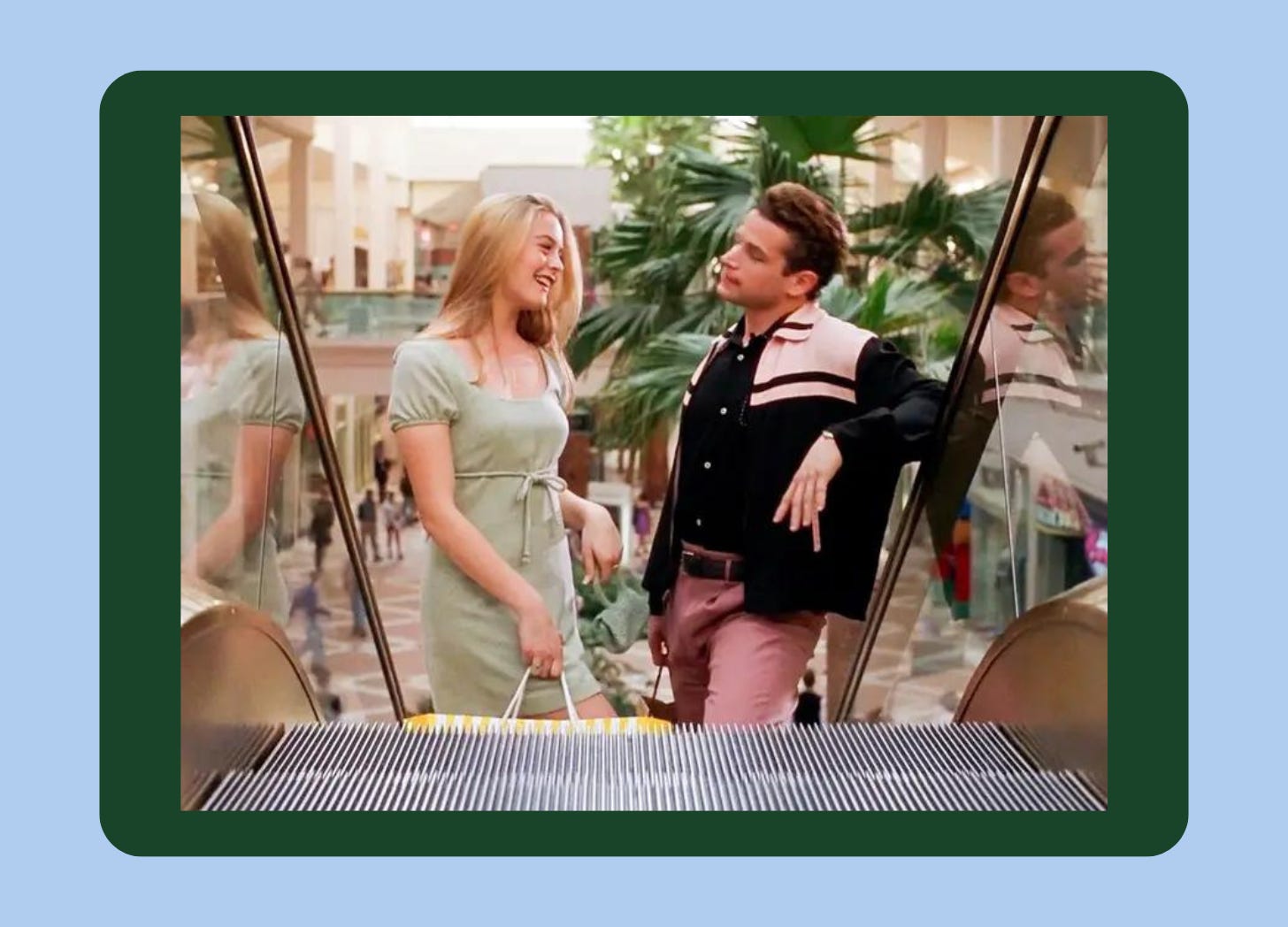

My favorite piece of mall pop culture is Clueless. Do you think Clueless is essentially about mall culture? (Also, do you think her closet organizer is an attempt to create a mall in her house?)

Mine too! The scene where Cher and Christian rise up the escalator with all their shopping bags is peak mall, the Queen and her shopping Consort.

I really loved the way you defined malls as selling innovation because they need it to survive. (“Malls sought innovation because they sold innovation; unlike other architecture that was built to last, malls were built to sell fashion and newness and they, too, had to turn over every decade or so, just as the Nashers predicted.”) Do you still see malls as places that can innovate? What do you think the most successful examples of innovation have been?

In the past, the food court, as previously discussed, and then, in the 1990s, the tweak of malls away from just shopping and toward entertainment, most famously at Mall of America with a whole amusement park in the center. As it happens, those innovations are the background for the two most important changes I’m seeing in malls these days. One, the food court isn’t just stuck up on the second floor anymore, now it is filling the atrium, or taking over the emptied-out department store space, and the offerings are broader, and fresher, and maybe there are incubator spaces for local food entrepreneurs. Two, while malls always had carousels, and soon added movie theaters, people are trying all sorts of active, family-oriented entertainments at malls, from pickleball, to BMX tracks, to trampoline parks, climbing walls, and so on and so forth. In all of these cases, these are things you can’t do at home.

I’m curious about what you’ve noticed in terms of the reaction to your book. You note the strong mall nostalgia in our culture, whether it’s Dan Bell’s Dead Malls YouTube channel or r/deadmalls on Reddit, though malls aren’t actually in decline (in part because they innovate). Do readers you’ve met or heard from still see malls as vital spaces or as sites of nostalgia? Does it vary by age?

The greatest variation seems to be in location. If you live in southern California, or central or north Texas, or many cities in the Midwest, it is very clear that malls are alive. Even if several malls in your area have died, there’s still one mall to rule them all, and for certain things you wouldn’t think of shopping anywhere else. In those places, it could still be the 1990s. If you’ve lived in a major city for a long time, or in places that never had high-end malls, it is very easy to not have been to a mall in a decade or more and have all your experience be in the past. I happen to be married to a native New Yorker, and have two New York kids, and they feel nothing about the mall.

Have you encountered snobbishness about malls either in researching the book or in talking about it?

Yes, in researching the book. People would say, Aren’t all malls dead? Or, Why would you want to write about those things? Or, aren’t they all the same? Most of that melted away once the book was written but I will say there is a category of guy, my age and older, that definitely still thinks malls, and a mall book, is not for them. Like, they get why someone could be interested in that but it could never be them. I had a remarkably similar experience with my previous book, “The Design of Childhood,” comments like, “I’m sure my wife would really like this book.” As if Gen X and Boomer men don’t shop, weren’t children, don’t have children …

As a side note, who is mall wave (like this video example) for?

I love mallwave, and I have always said my favorite day of research for “Meet Me by the Fountain” was the day I spent listening to one mallwave hit after another. The mood! But mallwave is not for me, a Gen Xer, it is for young Millennials who did not hear Toto’s “Africa” the first time around. Mallwave is a layered nostalgia experience where you hear an “old” song played as if in the hollowed-out space of the mall you [went to as a kid, worked in as a young adult, visited the last time you went home] so you get the double-whammy emotional effect of sound and spatial memories.

I love reading the comments on YouTube mallwave songs. They are all specific narratives about people’s first jobs, being in the mall after closing, and so on.

In your conclusion, you share an idea I love: “Imagine the mall being as physically embedded in place as it already is in culture.” There are a lot of mall fatalists who believe the form is dead, although as you note, they are still very much alive. What do you think it would take for malls to be as embedded in place as they are in our culture (even if just in our cultural imaginations?)

I hope that my book has, and will, nudge people in this direction, by treating malls as an architectural innovation with a long history, and tracing how many ways they show up in 20th-century American history. But I also see the current experimental era of malls as quite generative: In many places, developers are using malls to right some of the wrongs of postwar suburban planning, adding green space, housing, educational and medical facilities to malls and their parking lots. The community role that malls have always fulfilled becomes a lot more obvious, to more people, through these projects that physically build community around that big box in the parking lot.

You can find more of Alexandra Lange’s work here.

Call Me! (or not!)

I’d love to hear from you! Drop your thoughts in the comments to share with the Landline community, or reply to this email to contact me. You can also find me on Instagram, or email me. I don’t have a dedicated phone line yet (just like in my youth), but maybe someday I’ll achieve Claudia status and get a Landline.

Thanks for reading!

This is a free post for subscribers of Landline. Consider subscribing to the paid plan to get my weekly email of recommendations and links, a podcast episode, and more! You can also help me spread the word by sharing it with a friend who would love it. Thank you for being a friend!