A Deep Dive into the History of Blind Dating Shows: From Radio to Love is Blind

Does examining the history of blind dating shows tell us anything about Love is Blind (and our own pop culture)?

When non-social scientist Nick Lachey opened the first episodes of Love is Blind along with fellow non-relationship expert Vanessa Lachey in 2020, they referred to their show as a “social experiment.” Now, Nick Lachey is no Mark Zuckerberg (obviously), but this phrase smacks of “thought leader” energy and Silicon Valley-level hype about the ways a “new” idea can improve an old concept, in this case, how to find love. It’s not odd for a producer to pitch their show as a brave new concept when it’s likely an old setup in new clothes (or old wine in iconically new gold goblets if you will), but the recent hype around Love is Blind has me interested in “Blind Date” type shows that have come before, and what any of it can tell us about ourselves.

“Blind dates” as a phrase allegedly dates to the 1920s, popularized by college students. While I’ll get into the ableist implications of this phrase, I want to note at the outset that an interesting piece of the history is the shift in its meaning. Originally, a “blind date” referred to the act itself, of being set up by mutual friends etc. without setting eyes on one another. Later, the phrase “blind date” came to describe those on the date. I keep thinking about this shift when it comes to the setups on dating shows and wonder if the “blindness” looks different (pun not intended, just want you thinking about metaphor) for the setting of the shows and their contestants.

An interesting precursor to Love is Blind was Blind Date, a radio show that premiered in 1943 and ran through 1946. Produced before a studio audience, the show consisted of pulling six servicemen from the crowd, grouping them into three pairs and having each pair compete for a date with a model or actress. Standing on stage behind a wall that would prevent them from seeing their future date, they’d call her on a phone as the audience listened in and try to impress her in just two minutes. “Like most blind dates, these will be made over the phone. Sounds like Fun!” an ad described. After her phone calls, the woman would pick between the two men and head out for a night on the town at the swanky Stork Club. The winners got this date with the model, and a corsage to offer her. As a consolation prize, the unselected serviceman could win $5 by correctly answering a trivia question.

In a sample episode of the show from 1945, it’s clear that the show both wants to entertain and be part of the war effort. No matter how smarmy the men pulled from the audience appear, they will be going to the Stork Club with an underpaid model or actress by the end of the show (each received $50 for participating in the show and going on the date). In this episode, a woman revealed to the audience to be wearing a dress modeled on the American flag sits behind a wall waiting to be called by two servicemen. The first awkwardly aww shucks his way through his two-minute attempt to sell her on choosing him. The second, a man very proud to be from Brooklyn, tells her he’s looking for “a slick chick with a trigger figure.” What could this phrase possibly mean? Well, she asked, with barely disguised skepticism, “Trigger?” to which he responded, “In the service, we’re taught to squeeze the trigger.” Groan. Hoping to add some poetry to this . . . whatever the opposite of poetry is, he concluded “If you pick me, it’ll be like picking fruit from the tree that grows in Brooklyn.” Is this the origin of the pick me boy? What does that even mean? I can’t say. She picked date #1, seeming to confirm that this produce soured in under two minutes. Listening to this is a trip, and offers a window into wartime pop culture that was completely okay with objectifying women for #America. (The model in question was wearing a dress with a flag pattern and the host presented her to the two men at the end of the calls saying “You want to pledge allegiance to that flag?” to which one man responded “That’s what we’re fighting for!”) Listening to this was like watching Ben Affleck in Pearl Harbor, endlessly entertaining but ultimately confusing as to the cause of World War II. Not unlike that cinematic gem, it also made hay of racism against Japan by asking a trivia question for the $5 prize, “What’s another name for Japan?” The correct answer would have been “Nihon,” but the man simply said “Mud” to the applause of the audience and host. Just like watching my grandmother flirt at church, an episode of this show was both weirdly fascinating and ultimately cringeworthy. Interestingly, reviews of the show found it too risque. Noting that in one episode a man asked his potential date what kind of kisser she was, Billboard concluded its review saying “Since broadcasting is a family medium it doesn’t belong on the air.” Clearly, these reviewers would be legally dead if they heard the kinds of questions posed on the 90s classic Singled Out, never mind the fantasy suites of the Bachelor. I would love to see Jenny McCarthy with World War II vets, but then again, maybe not.

Why weren’t the servicemen allowed to see the woman in question, and vice versa? Intrigue? Sport? Replicating the audio-only experience of the radio they were being broadcast on? Hard to know why that concept felt so essential to this game. It seems that blindness here describes the situation of their meeting. Can we even call this a “date” if one of them is paid?

The next important moment in Love is Blind genealogy is The Dating Game. Iconically, every celebrity you can think of appeared on this show, which aired from 1965 to 1973 in its first run, and intermittently through the 90s in reboots. John Ritter, Sally Field, a future serial killer, this show had it all! Not unlike Blind Date, three bachelors or bachelorettes would sit on one side of a wall from their future date who would pepper them with truly chaotic questions to land on the date of his/her dreams, or at least of that day. Watching an early episode, like this one from 1967, really feels like I’m back in the pre-Woodstock era or at least on the set of American Dreams. How in the world are we supposed to find love if the questions we’re asking potential dates include “Bachelor number three, pretend you are Confucius, make up a special little proverb for me right now!” as this woman asks three men who truly just want to go to dinner and be on TV. The pressure of this question made me sweat. “People in glass houses should dress in the basement,” Bachelor number three replies, seemingly winning over the audience, and by extension, the bachelorette who picks him to go on a date. The prize is a night out at a Liza Minnelli show, which is a reminder that all of these shows are allegedly hetero, or at least never feature gay people, just our favored entertainers. YouTube has many excellent examples of celebrities who have appeared on the show through the years, including a non-white-haired Steve Martin (rare) and Karen Carpenter who is truly worthy of no man. (This reminds me I still really want a “lead sister” T-shirt.)

What seems to unite Blind Date and The Dating Game is the role of the audience. We’re really there to be entertained, and the contestants are performing, or trying to match, with us. I can hear it in the Brooklyn soldier playing to the audience with his smarmy Betty Smith references and “trigger” pickup lines, and in the way the men sweat under TV lights to think up great proverbs on the spot. For their efforts, Blind Date gives a thrill to servicemen in wartime, and The Dating Game gives 15 minutes of fame to contestants who offer bios as varied as “future doctor who loves to surf, ski, and listens to jazz.” If this man was pitched to me, I’d assume his name was Barbie.

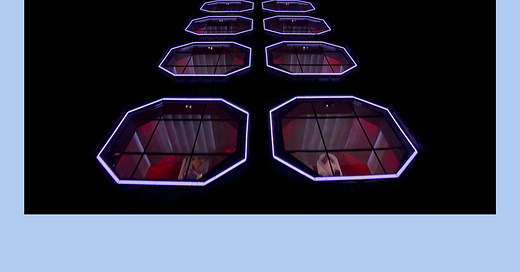

What, then, is motivating Love is Blind? If blind dates on radio and TV long predate it, what exactly is new about this “social experiment?” Is it just Blind Date or The Dating Game in new clothes, or pods? The contestants really act like sitting on opposite sides of a wall and carrying on dates that start at ten minutes and get longer over the still-brief window of the show is revolutionary. Is it the presence of Nick Lachey? Is it the fact that we aren’t there in the pods with them? No studio audience and no visible crew members in the pods seem to emphasize the intimacy of these conversations between strangers. The topics of conversation seem to be singular as well, with the dates coming in with notebooks where they’ve written questions that they believe will help them find their future spouse. Cuddled up on couches with blankets, drinking goblets of wine or who knows what, they seem purposefully domesticated as they weed through prospective partners. What initially sets this show apart is the seriousness of conversation topics. No one is prompting anyone to invent a proverb. Instead, people ask near strangers how many children they want to have or about their childhoods.

The seriousness of the conversations with almost no preamble makes it even more memorable when contestants appear casual in the midst of these “intimate” convos. Raven, one of my fave contestants, iconically did jumping jacks as her date, Bartise ( the human version of the thumbs-down emoji) reveals a vulnerable story from his past (this is feminist performance art). Tiffany, another great contestant, fell asleep while her future spouse Brett was explaining why they were a perfect match and saying “you are special to me.” I can’t blame her because that couch looked comfortable, and she was tired. Also, falling asleep while men on reality shows struggle to describe basic human emotions feels like a karmic healing of the men of 1945 being gross on Blind Date, never mind the chaos of the use of tongs and blue lights on shows from my teenage years like Room Raiders. (Someday I will write about my lifelong love affair with the contestant bios on Next!)

Unlike Blind Date and The Dating Game, contestants seem to be focused on finding someone for a long time, not just a good time. If this sincere “experiment” to find a spouse is what makes it unique (apart from the goblets), I have to wonder what work “blindness” is doing here.

The phrase “Love is Blind” itself allegedly dates back to Chaucer. In his “Merchant Tale” from 1405, he wrote “For loue is blynd alday and may nat see.” Demonstrating that reboot culture was alive and well way before the invention of Marvel, Shakespeare made much use of the phrase, and in The Merchant of Venice specifically,

But love is blind and lovers cannot see

The pretty follies that themselves commit;

If we want to take art history into account, we could cite paintings of Cupid with covered eyes which you can find in all kinds of western art and prints sold at Marshall’s (said as a lifelong Maxxinista/Marshall’s fan). The origins of the phrase don’t matter so much as the realization that our culture has long normalized equating being in love with blindness. Why? In most uses, it suggests that being in love robs lovers of their ability to “see” reason, or influences us to make choices that are not in our best interest. (See every contestant on every dating show ever, and likely many people you know IRL). This imagines the people engaging in the situation are “blind,” but what does it mean if the situation of the meeting is “blind?” If we’re in the pods, and we can’t see each other, does that mean that our choices somehow become pure and objective? Do we turn into lady justice, also imagined as blind as a form of virtue signaling? I.e., does the “blind date” scenario mean we turn into people who can’t “see” color, or any other kind of biases?

Any casual viewer of Love is Blind (or any other blind dating show) knows this isn’t the case. One of my fave contestants ever, Deepti, who deserves only good things in this life, was subjected to gross questions by her eventual match, Shake, designed to draw out a description of her body and appearance. If the premise of the show is that awareness of a person’s appearance has perhaps “blinded” contestants to their greater suitability as partners, therefore encouraging them to enter this “experiment” where that barrier is removed, why are men so thirsty to find out what women look like? On the most recent season, Chelsea tells her eventual match Jimmy that she has been compared to Megan Fox, setting up later awkward scenes when Jimmy confronts Chelsea about the truth of that comparison. It is as gross as it sounds. For the record, she said she didn’t see the comparison, but just shared similar hair and eyes. However, inviting that comparison in the mind of a person who has never seen you may be a way of tipping the scales in your favor. Notably, this appears to be part of the behavior of some women on the show to court a proposal in the pods from men who will mostly go on to disappoint them IRL. Also in the most recent season, the relationship between Clay (a man who desperately needs therapy) and AD (a person for whom I only wish great things) created a lot of conversation about colorism and the weight of what AD had to bear in her relationship as a Black woman held to impossible standards by an immature man. In 1953, the Evening Star newspaper ran a piece on blind dates. “How can a boy keep from feeling like a fool on a first date?” the reporter asked. “Act more adult,” said girls polled on the subject. Indeed.

What it all comes down to for me is the mess of metaphor. Metaphors often reveal our culture and our values. Susan Sontag famously wrote about Illness as Metaphor concerning her own experience of cancer in the 1970s, noting that the language of “invasion” and “war” seemed to complicate and make exceptional this particular disease and charge those living with it to “fight.” We can imagine how tragic it is when a loved one dies of cancer, especially if they have been exposed to this kind of martial language of their disease which might suggest they’re “losing” their “battle.”

In a recent essay in Aeon, “How Changing the Metaphors We Use Can Change the Way We Think,” Benjamin Santos Genta noted the harm the unconscious use of metaphors can cause in our world. “Metaphors are (metaphorically) woven into the fabric of our language and thought, shaping how we grasp and articulate abstract concepts,” he wrote. Often, we translate our ideas from abstract thoughts into metaphors, helping us to construct our reality. Think of being at the doctor and trying to explain what a headache feels like. Is it like a baseball cap that’s on too tight? Does it feel like a hammer?” These abstract metaphors can help us communicate something real to our doctor to lead (hopefully) to a concrete understanding and treatment. This is a positive use, as opposed to inadvertently making cancer patients feel like “losers” if they aren’t “warriors” whose bodies are “winning” the battle against disease.

The language of “blindness” itself is particularly jarring because it’s so often used as a negative. “The blind leading the blind,” etc. It signals ignorance, stupidity, lack of insight or self-awareness. Paging Oedipus, or that Sandra Bullock movie I won’t watch because it looks scary. “In all their variations, our cultural metaphors surrounding disability increase its stigma while often obscuring the actual experiences of people living with disabilities,” scholar Juliane McCobin writes in “Disability and its Metaphors.” We miss them because they are so prevalent and often unchecked.

You might be thinking at this point. Woah, Mary! We’re talking about blind date reality shows. I hear you, but I am invested in reality TV! I take any enterprise that’s trying to talk about love seriously, in part because I know it’s so hard to do. Virginia Woolf once wrote we have hundreds of ways to describe what it feels like to be in love, but few to describe a headache. I still think we have no idea how to describe love, but I love seeing people on TV try. I am interested in what they think the “social experiment” of metaphorical blindness will offer them when it comes to love.

For all the nuance the show uses in promoting itself, and that the contestants seem to think defines this experience, there is really nothing much new in Love is Blind. The metaphor of “blindness” here seems to invoke the idea that not seeing your partner can open a person up to all kinds of matches they would otherwise not select for themselves. In removing their own “blinders,” they can find love. Harmful metaphors aside, the premise rarely offers that kind of access to people who are radically different from a contestant’s type. Partially, this is because of casting. This is a show that casts thin people (mostly) and beautiful people. Nothing radical here. Contestants also use conversational interviews to get at the physical descriptions that clearly matter to them in terms of attraction. In the later stages of the show, when the couples meet and go to a resort and then live in an apartment together, we see the ways the issues of sexual attraction, race, religion, politics, family cultures, and more all come into play.

No language of disability can disguise the humanity of all involved, for better or worse. Men use their questions to trick women into offering a physical description. Women too desperate for mediocre men are overly agreeable to the men who feel chastened by other dates. It’s interesting to note that women will sometimes go out of their way to offer that they want to be submissive to men as head of household, for example. Many seem to be posing for the audience at home, or at least potential sponsors, hoping to shape their own storylines so far as they can control.

Watching the “love” play out on these shows demonstrates that its metaphor is misplaced. It is hardly “blind” if the producers take that to mean disguised, impartial, unpredictable, etc. It is clearly chaotic, definitely messy, and ultimately human.

It’s worth pursuing a new metaphor to describe dating someone we’re set up with either by friends or producers. As Benjamin Santos Genta reminds us, “A collective effort to notice and change the metaphors we use has enormous potential to reduce individual and societal harm.” More than that, in the case of Love is Blind, it helps remind us to question the alleged innovations of “social experiments” that claim to offer something new. Arranged marriages and setups by friends are not new. Like Facebook, itself a reimagined version of a hard-copy facebook colleges would circulate to incoming freshmen as a way of introducing a new class, technology applied to dating has resulted in the same awkwardness of dating, just with new packaging. Now, users can swipe through photos and make snap judgments about appearance instead of judging how their date holds a fork on a first date. The addition of technology or, in the case of Love is Blind, the setup of a “social experiment,” doesn’t actually change the snap judgments and biases we bring to dating. Dating brings out the best and worst of humanity, and on Love is Blind, we see that same dynamic play out, just with better merch.