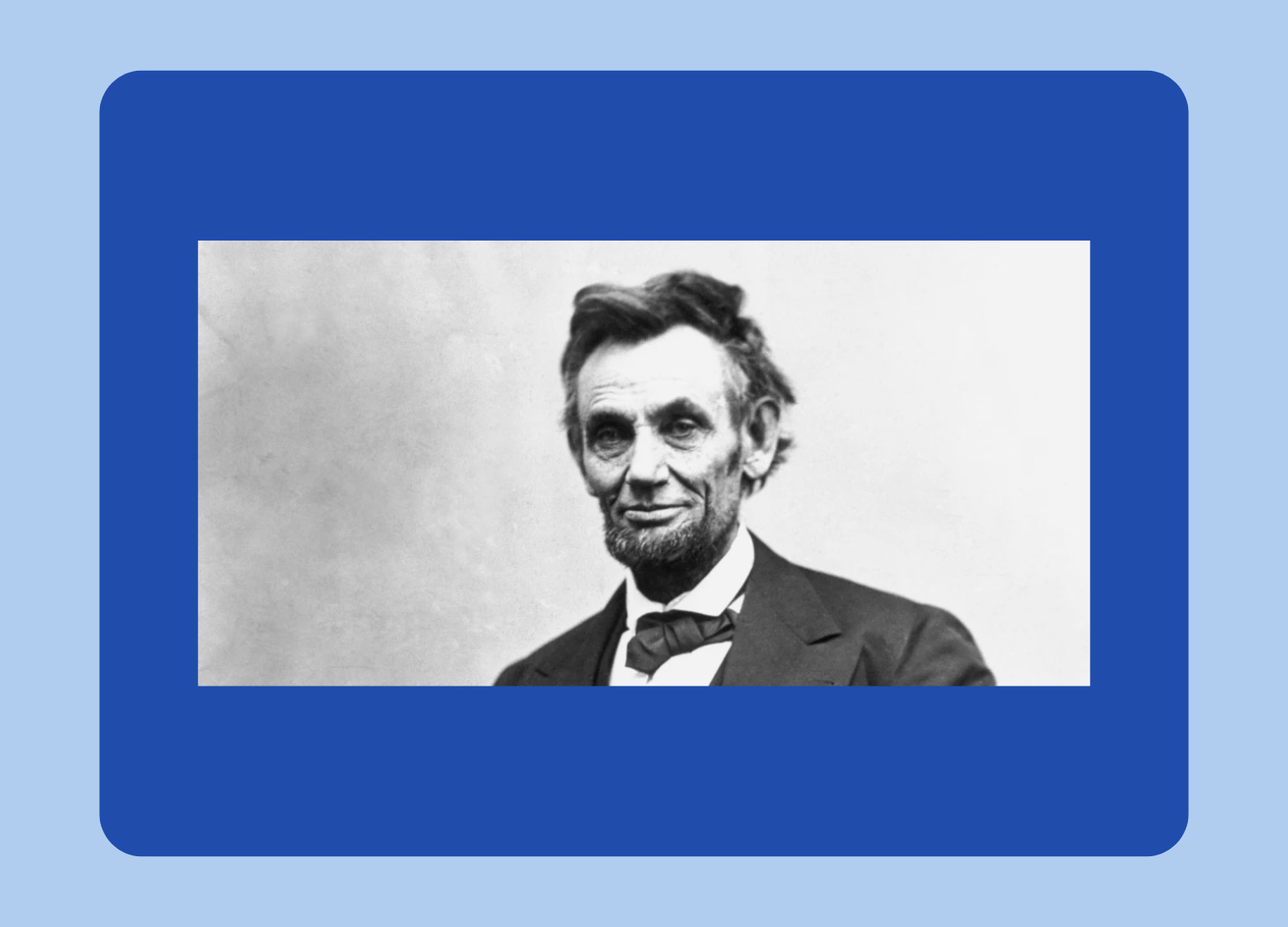

Lincoln, Fan Fiction, and Queer Museums: A Deep Dive into Possibility

Talking with Haley Bryant about queer possibility at President Lincoln’s Cottage

This is a free post for subscribers of Landline, a pop culture and history newsletter for people who care about the Titanic, and the Kate Winslet vehicle of the same name. Consider subscribing to the paid plan to get my weekly email of recommendations and links, a podcast episode, and more! You can also help me spread the word by sharing it with a friend who would love it.

After my interview with Margaret Middleton last week, I wanted to follow up by highlighting folks who are actually doing the work of queer possibility. For the next three weeks, you’ll receive a profile of someone who thinks about queerness in their professional work whether in archaeology or museums. This could mean exploring what house museums as spaces can tell us about queer experience or studying President Lincoln by actually being open to the question of just what was going on with Joshua Speed (aka the topic of a fan fic I may write someday).

My first guest understands the importance of these conversations, especially the ways they can draw the public into discussing queerness by using a “famous” person like Lincoln to do so.

Name: Haley Bryant

Organization: President Lincoln’s Cottage (PLC)

Can you tell us about the museum where you work?

President Lincoln’s Cottage is a historic house and museum located on the grounds of the Armed Forces Retirement Home in the Petworth neighborhood of Washington, D.C. The house was built in 1842 as a private residence and then sold to the government, along with 250 acres of land, to the federal government and turned into a retirement home for military veterans in 1851.

In 1862, Abraham and Mary Lincoln - accepting an invitation from the Home - picked up and moved to the Cottage for the hot, summer months of 1862, ‘63, and ‘64 along with their youngest son, Tad, and a whole mess of soldiers.

The Cottage at the Soldier’s Home is the place that Abraham Lincoln conceived and drafted the Emancipation Proclamation.

We like to say that today, as in the 1860s, President Lincoln’s Cottage is a “Home for Brave Ideas”. We host scholars, activists, and community members to speak and present their work here; we collaborate with other historic sites in the DMV - like Ford’s Theater, the Frederick Douglass House, and Tudor Place - to offer educator workshops, and we put on exciting, boundary-challenging exhibits like Prison Reimagined. We also offer educational programming for schools and groups of all ages, including our annual Students Opposing Slavery Summit that brings students from around the globe to learn how to combat human trafficking with D.C. experts.

What drew you to this work?

Although none of my degrees are in history, and I have only recently finished reading my first biography of Abraham Lincoln in the last year (they tend to be very, very long…), working at PLC is the natural next point in my professional museum journey. I have now experienced the “Lincoln Shiver”, and regularly fall deep down the rabbit hole of Lincoln lore - but that’s not why I love working here as much as I do. What drew me in from day one is the conversational approach to tours that PLC interpreters are trained in, the clear social justice framework the staff applies to all projects, and the willingness to do what is risky and what is right in the face of a society and a field that much prefers their museums to strive for “neutrality”.

I get to tell silly stories about Lincoln, his son Tad, and their goat Nanny, but I also get to think with visitors about things like the direct link between the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and our modern-day carceral system. That’s the kind of work I believe all museums can and should be doing, and it’s the work I get to do every day at PLC.

What is one of your favorite aspects of the museum? This could be an object in its collections, a juicy anecdote you’ve stumbled on in research, or a treasured visitor interaction you’ve witnessed, etc.

There’s a story we tell in the Parlor about a gentleman named Colonel Scott (rather “he” tells it himself, we play audio of Scott’s diary for the visitors). Scott came to the Cottage one evening in 1862 - just days before the Second Battle of Bull Run - with an urgent request for the President. His wife had perished in a terrible boat accident on the Potomac, and he needed the President’s permission to retrieve her body from the locked-down area around the river. Scott also reveals that he’d already sought this permission from the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, and been told ‘no’.

Lincoln’s response was less than gentle. He reminded Scott that he’d broken Chain of Command by going around Stanton, and he urged Scott to recognize that “suffering and death are upon us all.”

Visitors are often silent when Lincoln’s response ends. It doesn’t jive with the mental image they have of Lincoln as someone who would help anyone in need, a man who had suffered his own losses and would recognize Scott’s tremendous grief. Usually, though, they understand that Lincoln’s answer is practical, and that, of course, he was under immense pressure and couldn’t help every single person who came calling with a request like Scott’s.

The story doesn’t end there, though. According to Scott, he went back to his hotel in defeat and was woken the next morning by a knocking on his door. Lincoln was there, and he apologized to Scott for being a “brute”, tells Scott that he has spoken with Stanton and arranged everything, and offers his own personal carriage as conveyance and himself as a companion as Scott goes to get his wife’s body.

If I had a dime for every grown man reduced to tears by the end of this story, I would have some dimes! Truthfully, it seems to move people in some pretty strong ways, positively or negatively. Before we leave the room, I ask visitors to reflect on the last time they noticed a person in a position of authority apologizing for something they’d said or done, and the last time they themselves had apologized for something. I ask them if the way they feel during that reflection compares to how they felt listening to the story of Lincoln and Scott. When the vibes are right and everyone is locked in, this can be a really transformative moment in the tour. I know I’m transformed by it every time.

What are the kinds of narratives traditionally used in interpretation by the museum about the people who lived there and/or about the significance of the site or its collections? How has the interpretation changed over time?

I think our interpretive lens can be summed up by a comparison between our life-size statue of Lincoln, standing next to his horse and ready to ride out for a day’s work (or coming home after one - you decide), with the statue in the Lincoln Memorial. Whereas the Memorial literally puts him on a pedestal where he sits cooly self-possessed and many times larger than life, our statue allows you to see him more like he really was.

We invite our visitors (who include everyone from tourists just looking for something to do, to renowned Lincoln scholars) to get to know Lincoln the man instead of Lincoln the Emancipator, or Lincoln the President. We tell stories about Tad Lincoln putting on his child-sized Union uniform, performing drills with the infantry company on the Cottage’s south lawn, and how even his father called him Third Lieutenant (a fake title); we talk about Lincoln’s relationships with the household staff of the Cottage and especially his White House Chief of Staff, William Slade; we talk about the small moments that, when added up, create a more fulsome picture of a complex individual who made very difficult decisions.

More specifically, the Cottage is the place where Lincoln drafted the Emancipation Proclamation, so our interpretation circles around how this place influenced his thinking. Lincoln commuted to the White House and back nearly every day he was living in the Cottage, and along the way he stopped to talk to all sorts of people, including ambulance trains packed with soldiers on their way to the hospital and formerly enslaved people living in Contraband Camps. We know these conversations helped him solidify his thoughts around Emancipation and the end of the war.

The Cottage has only been open to the public since 2008 (preservation only began in 2000). According to staff who have been here since almost day one, and visitors who have kept coming back over the years, the interpretation has changed tremendously. Primarily because we’ve learned so much more about this place and what it meant to the Lincoln family, but also because the staff have consistently pushed themselves to go deeper and expand our own understandings of what “good” interpretation is and what our guests are seeking when they visit.

Is there any specific interpretation you have to deal with in the mountain of scholarship on Lincoln?

It’s not hard to tell a balanced story about Abraham Lincoln. Up until the moment of his death his views on slavery and race were evolving. John Wilkes Booth felt so motivated to do what he did because he’d heard Lincoln imply in a speech that he was considering enfranchisement for Black men. Considering it. And only for some of them, not all of them. And only in certain circumstances. On the other hand, he did successfully pass legislation outlawing slavery in the United States…except as punishment for a crime.

He was a teetotaler with a sense of humor that sometimes rubbed people the wrong way and he had a deep, dark streak of melancholy. He loved talking to members of the public and he loved his children, but he failed to stay the executions of 38 Dakota men sentenced for their involvement in the Dakota War of 1862 because, as he explained to the U.S. Senate, he was worried if he acted with too much clemency it would stoke the fighting all over again.

Heck, the Emancipation Proclamation - arguably his most infamous achievement - didn’t really end slavery at all. But he consciously made that decision because he feared the loss of support from the Border States, and by proxy, the loss of the war for the Union.

What is difficult for some people is hearing a balanced story about Abraham Lincoln. More than any other President, certainly, and more than most historic figures, Lincoln becomes a catchall for our collective moral and social baggage. Because there’s so much about him that we’ll never know, because he didn’t leave us diaries and journals full of his inner thoughts, it’s very easy for us to project our own beliefs on him. In other words, he is the best president America has ever had, on the balance he was a good person. And if we’re good people too, that must mean Lincoln thought like us, worshipped like us, loved and talked and dreamed like us. I understand this impulse, but it can be hard for people (myself included) to see past these opinions we hold as self-evident truths to the human being underneath.

What role, if any, has queerness played in stories the museum tells or in questions the museum gets from visitors?

The most direct role queerness plays - the one that is so obvious I often forget it - is that many of the staff of PLC are queer and we are welcome and encouraged to bring that part of our identity to our work every day. We wear our pronouns on our name badges, for example, bring partners to work functions, and talk openly about queerness in the break room and in meetings.

Interpretation-wise, there is a “rumor” that has followed Lincoln for a very long time about his sexuality and the potentially queer relationships he maintained with a few important men in his life- one of whom he met and interacted with here at the Cottage. Visitors - especially younger visitors - ask about this pretty often, and instead of brushing them off, PLC staff decided to dig into this question so we can offer those visitors a meaningful answer. Plus, we were just curious!

[I’ve also talked more for Landline’s Show and Tell series, and you can learn more about PLC’s interpretation of this part of Lincoln’s life on our podcast].

How has the response to questions about queerness changed over time? How did the museum determine how it would discuss queerness?

From what I know of the Cottage’s early days (way back in the early 2000s), the interpretive approach has always been oriented toward inclusion of marginalized voices and historical nuance. Once the staff realised that Lincoln’s sexuality was something a lot of folks were curious about, they decided to use the tools at their disposal to actually investigate and offer visitors something more than a shrug, or a “we’ll never know!”

I wish I had been a fly on the wall during the earliest discussions about how our interpretation would incorporate Lincoln’s sexuality, but alas. What I do know is that the effort has been really spearheaded by our Associate Director of Learning, Joan Cummins, who - as a queer museum professional themself - recognizes the tremendous value and potential in bringing discussions of queerness (Lincoln’s or otherwise) to the fore at our site.

How do you see the museum as a site for discussions of queer history?

If we can stand in the bedroom of Abraham Lincoln’s summer residence, where we know he occasionally shared a bed with his friend and bodyguard Captain David Derrickson when Mary was traveling, and talk about the Queer Possibility of his legacy - it feels like we can talk about the Queer Possibility of anyone’s legacy. He’s a historical ‘big fish’ if you will, and if we can imagine queerness - in whatever form it took in Victorian Illinois - for him, I think we can imagine queerness for anyone. Even ourselves. I hope we can become a place that people feel eager and safe discussing museological and historical queerness in all its contexts.

The Cottage is also unfurnished, which is uncommon for historic houses. This was a very thoughtful interpretive decision made by leadership before the site opened to the public in 2008, primarily because no furniture from the time remained and we have no idea how the house was furnished. Instead of filling the space with stuff for the sake of stuff, we fill it with stories about Lincoln and his family. The house is sort of a ‘blank canvas’, as a result. Visitors are active participants in co-creating their experience and are invited to imagine the conversations and interactions the interpreters share with them - we favor dialogue over names and dates. There’s so much space for people to bring all of themselves into the space, and to allow themselves to expand to fill it.

I also want to be wary of detaching ‘queerness’ from its very specific historical contexts and contemporary meanings, but taking a ‘queer’ approach to museum interpretation is also one way to open up possibility around all sorts of other things like: parenthood and family, grief and loss, community and mutual aid, creativity and art, spiritualism and religion, and the list goes on! Museological queerness is a practice and a process, not just an addendum to existing interpreter notes or an extra bit of wall text in an exhibit.

What are the challenges to doing queer history in this space?

I had a long conversation about this question with my colleague, Joan, whose been with PLC much longer than me. The two interpretive challenges they identified were that people often struggle to perceive the past as simultaneously similar to and different from their present. While we might not be able to apply modern terms to historical figures’ intimate relationships, and our ways of understanding identity and presentation have evolved over time, the ways people have lived and loved together on a fundamental level have persisted. It’s not helpful or accurate to say “they didn’t use the word ‘gay’ back then, so…”, brush our hands off, and move on as if there isn’t a whole universe of nuance to dig into there.

The other interpretive challenge Joan mentioned is that people often have an understanding of history as linear. There’s a persistent idea that things are far better today for queer and marginalized communities than they were ‘back in the day’ and that the farther back we go in time, the worse off they were, proportionally. Historians will tell you that isn’t really how it’s worked for any social issue or community. Working with those sorts of preconceived notions and cognitive dissonances can be really challenging when your end goal is to help people re-orient themselves (in the sense of Sarah Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology) to the idea of historical queerness. People also like solid answers, even if it’s not the answer they were expecting or one they agree with. Our answer to the question of Lincoln’s sexuality will always be, until someone uncovers more evidence, squishy and indefinite. That can be hard to sit with.

Joan also mentioned that there are plenty of people who visit us who are starting from zero (or less than) in terms of their knowledge, familiarity, and comfort with queerness. This requires an extra measure of education that our interpreters just don’t have time (or emotional bandwidth) to do in order to get people to a place where they can grapple with the idea of historical queer possibility.

I tend to think more infrastructurally about challenges. In the “space” of PLC, I really feel that the only limit is our imagination (and our resources). We’re lucky to have a board of directors who are supportive of our interpretive approach (truly the key to any museum’s success), and so far our commitment to exploring Queer Possibility hasn’t impacted any funding opportunities or anything like that. On the contrary, I think we’ve expanded our pool of members and donors because we make an effort to explore this part of Lincoln’s history. We just tabled at the D.C. Pride festival and had the most wonderful conversations with people who we hope to see soon on a tour.

All of that is not to say we don’t have our share of critics and detractors. The Heritage Foundation, for example, has publicly taken umbrage with our - as they put it - concerning promotion of Social and Emotional Learning and Critical Race Theory. We definitely get the occasional visitor who doesn’t have any interest in having their assumptions about Lincoln, the Civil War, and enslavement challenged. Overall, though, with strong leadership, a very clear mission and ongoing staff training we’ve met those things head on and, I believe, welcomed those folks in for a productive conversation.

Zooming out even further to the “space” of the museum field or historic house world, of course there’s long been resistance to acknowledging queerness of any kind, even when the evidence strongly suggests its presence, which is deeply rooted in homophobia and transphobia, colonialism, and capitalism.

What are the benefits?

Our skin has cleared, our debt has been forgiven, our pillows are somehow always flipped to the cool side … In all seriousness, the benefits are infinite. Our queer staff get to make a more personal connection with our content, and therefore help our visitors make deeper connections. Our visitorship is larger and more diverse because more people feel welcome here and see themselves in the history we interpret. I think people also leave feeling empowered to ask questions they’ve never seen asked in a public forum, but that they’ve been holding on to quietly. What is most exciting to me as a museum scholar is that we are actively contributing to the canon of Lincoln scholarship, too, because the interpretation we do is solidly rooted in the historical sources and previous scholarship that we have access to. Public history is so cool.

I think there are also invisible and less expected benefits to enthusiastically taking on Queer Possibility in a space like Lincoln’s Cottage. Queerness as an ontology - that is, a way of being in the world - requires that people reorient themselves to everything in their lives. Not just definitions of sexuality and gender. It necessitates that people reorient themselves toward the other people in their orbit. I think the Cottage’s enthusiastic embrace of queerness as an identity marker, as an interpretive category, and as a museological frame is directly tied to the success of our unionization efforts and our positive, supportive workplace culture.

Why are museums and historic sites such a great place to explore this topic?

Are museums still the most trusted public institutions, or has that gone out the window? Either way, I think most folks go to museums expecting to learn something that is true, or at least supported by evidence. Museums have the responsibility to tell stories rooted in truth, but unlike other institutions like academia, news outlets, etc., they have tremendous creative freedom to tell those stories in ways that spark their visitors’ imaginations and curiosity. Museums and historic sites aren’t just storehouses for cool stuff - they’re reliquaries, memorials, temporary or long-term homes for ancestors, spaces of mourning and celebration, community hubs, and so much more. The work of the museum happens in all those modes, not just when a visitor reads an exhibit label.

Museums can be both a window to the past and window to our own world. With that in mind, what can the idea of “queer possibility” coined by Margaret Middleton as a guide for museum interpretation offer by way of hope for how we can interpret other kinds of spaces and institutions where we spend our lives?

I think I’ve said plenty on this already, but I will add that I think the idea of queer possibility is so joyful! It really is so much more present and future-focused than past-focused. In asking us to reckon with facets of history as if they’re big ‘ol question marks and helping us to feel more comfort with the unknown/unexpected, it allows us to envision our own anxious, uncertain futures as overflowing with potential.

Has anyone ever written fan fiction about Lincoln? Should they?

Silly of you to even ask! Of course they have! A cursory search on Archive of our Own returned 303 results - honestly, far fewer than I anticipated. You’ve got everything from “Historical Real Person Fiction (RPF)” to Abe making a guest appearance in the Teen Titans universe. Reader, I suggest you tread carefully if you too go searching. To your second question - silly of you to even ask! Of course they should! I’m a staunch believer that transformative creative works (i.e. fanfiction, fanart, etc.) are incredibly valuable forms of expression and should be protected! I think Abe would have loved AO3, honestly. Besides, Lincoln is already such a mainstay in our mainstream media - just think about Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, or the season’s most hotly anticipated broadway debut from national treasure, Cole Escola: Oh, Mary! Not only has he become the vessel for all of our moral and social anxieties, but we’ve been comfortable for a long time taking him entirely out of context and turning him into a character for our entertainment. I think there’s room for that to exist right alongside the earnest, thoroughly researched interpretive work that sites like PLC do every day!

Call Me! (or not!)

I’d love to hear from you! Drop your thoughts in the comments to share with the Landline community, or reply to this email to contact me. You can also find me on Instagram, or email me. I don’t have a dedicated phone line yet (just like in my youth), but maybe someday I’ll achieve Claudia status and get a Landline.

Thanks for reading!

This is a free post for subscribers of Landline. Consider subscribing to the paid plan to get my weekly email of recommendations and links, a podcast episode, and more! You can also help me spread the word by sharing it with a friend who would love it. Thank you for being a friend!

Note: All books referenced in Landline can be found in my bookshop.org storefront from which I earn a small percentage of all books purchased.