From Hot Frosty to History: What Snowmen Reveal About Us

Making Meaning of Snowmen: From Renaissance Art to Netflix Hits

This is a free post for subscribers of Landline, a pop culture and history newsletter for people who care about the Titanic, and the the Kate Winslet vehicle of the same name. Consider subscribing to the paid plan to get my weekly email of recommendations and links, a podcast episode, and more! You can also help me spread the word by sharing it with a friend who would love it.

I never thought I’d spend so much time thinking about snowmen.

What started me on this opus? Like most things, something I watched for fun.

Minding my own business, I watched Hot Frosty with a friend a few weeks ago. I support Lacey Chabert, even if Hallmark-style Christmas movies aren’t necessarily for me. There is something about the uncanny valley/alternate universe-style reality of these films that always makes me feel strange. I’ve usually attributed this to not vibing with straight pop culture, but Hot Frosty really sent me. This “film,” starring the hot veterinarian from Schitt’s Creek and Lacey Chabert, depicts a snowman come to life with the magic of a red scarf to teach a grieving widow the meaning of Christmas/love/properly working HVAC systems (hard to say tbh). When I watch something and it makes me feel insane/crazed/angry/happy or any variation on a strong feeling, I can’t just let it pass. I have to investigate, Jessica Fletcher-style. So began my journey into the histories of snowmen. Like most things, snowmen aren’t inherently interesting. It is the meanings and stories we invest in them that are.

For example, when Hot Frosty first debuted a few weeks ago, some wrote reviews that flagged the movie as a sample of a schlocky genre (“the abominable snow movie,” the New York Post called it). One used it to talk about the role of these movies in letting women feel feelings and cry, as one reviewer said this movie did for her personally. (How?!) Rebecca Onion at Slate talked about the value of these movies for women who want a world in which they don’t have to deal with men and their complete lack of socialization. A snowman come to life, for example, will not text “you up?” or get vague when you ask him where he was on January 6th. These “cinnamon roll” leads, Onion notes, are overly sweet and present as sexualized objects of attraction for women without overtly sexualizing their female costars in turn. This, as many reviewers note, presents both simple and safe worlds for women to escape to where they can find the men not available elsewhere. That drives both their appeal and their sadness.

What these assessments leave out is the “why” or “what” of snowmen themselves. I get how Hallmark suggests a kind of story in our minds, but what work does a snowman do? What kinds of stories are they used to tell? I had to find out.

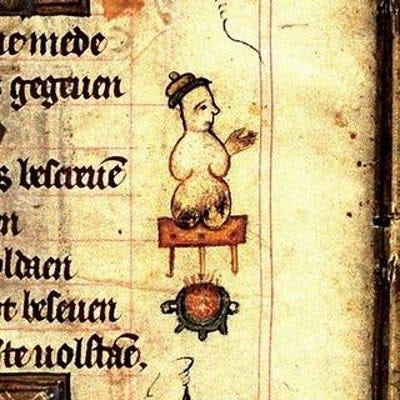

The first recorded snowman appears in a Book of Hours dating to 1380. According to artist and writer Bob Eckstein, the illustration of a snowman in the margins seems to be melting in front of a fire, symbolizing the persecution of the Jews. Not great.

Eckstein’s history records snowmen throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, with Michelangelo creating a breathtaking snowman in Florence for the Medicis, for example. It makes sense that artists would be associated with early snowmen as it was an art form drawing on a readily available medium and offering easy public consumption. If you ever want to feel small, make a snowman next to a person with a modicum of artistic talent. It will shake you to your core.

Snowmen are far more interesting as vessels for messages than as mediums, however. A festival in Brussels in 1511 featured 110 snowmen, sculpted in protest of the city’s government. Called “The Miracle of 1511,” residents sculpted snowmen in pornographic and satirical tableaus to protest the widening gap between the ruling House of Habsburgs and the poor. I’m not sure how creating "a snow virgin with a unicorn in her lap" called out the Habsburgs, but I’ll trust that it made a statement. Sex work is work, and sex work snowpeople enticing visitors to the city’s red light district (as some did during this festival) must have appeared like a seasonal wax museum or advertisement that could cause frostbite.

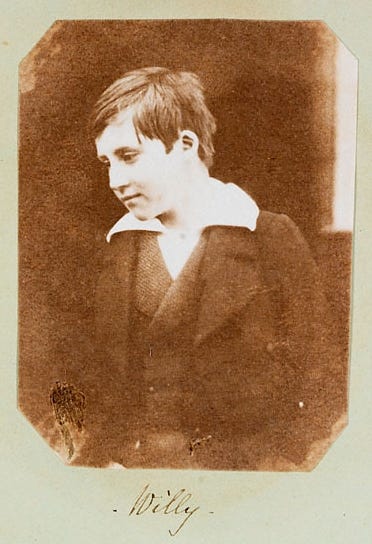

The idyllic image of children making snowmen dates back to 1853 when Welsh photographer Mary Dillwyn captured what is believed to be the first photograph of a snowman. Dillwyn favored a smaller camera than other photographers of the period (mostly men), and I could say something here about women not caring about the size of their cameras, but I’m moving on. What is important about Mary’s gender is that the relatively shorter exposure time required of her camera along with her position in mostly domestic spaces created opportunities to capture intimate family moments as they happened, like her nephew’s smile (believed to be the first smile caught on camera).

The advent of photography created not just family keepsakes, but public documentation of snowmen in broader culture.

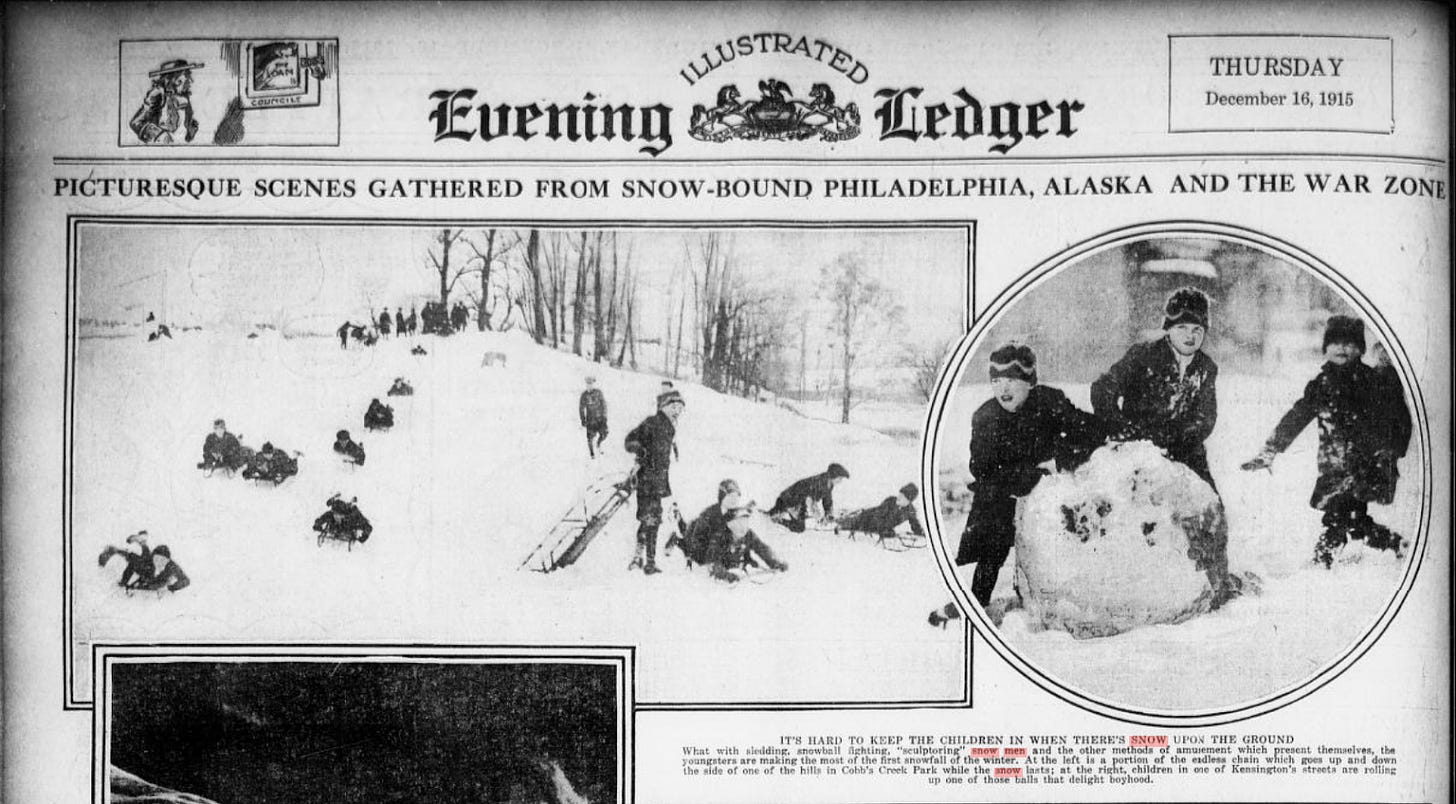

This 1905 spread, for example, captures the artistic submissions to a festival in Germany. By 1915, building snowmen was understood as a classic activity for boys (where are the girls?) in this Philadelphia paper.

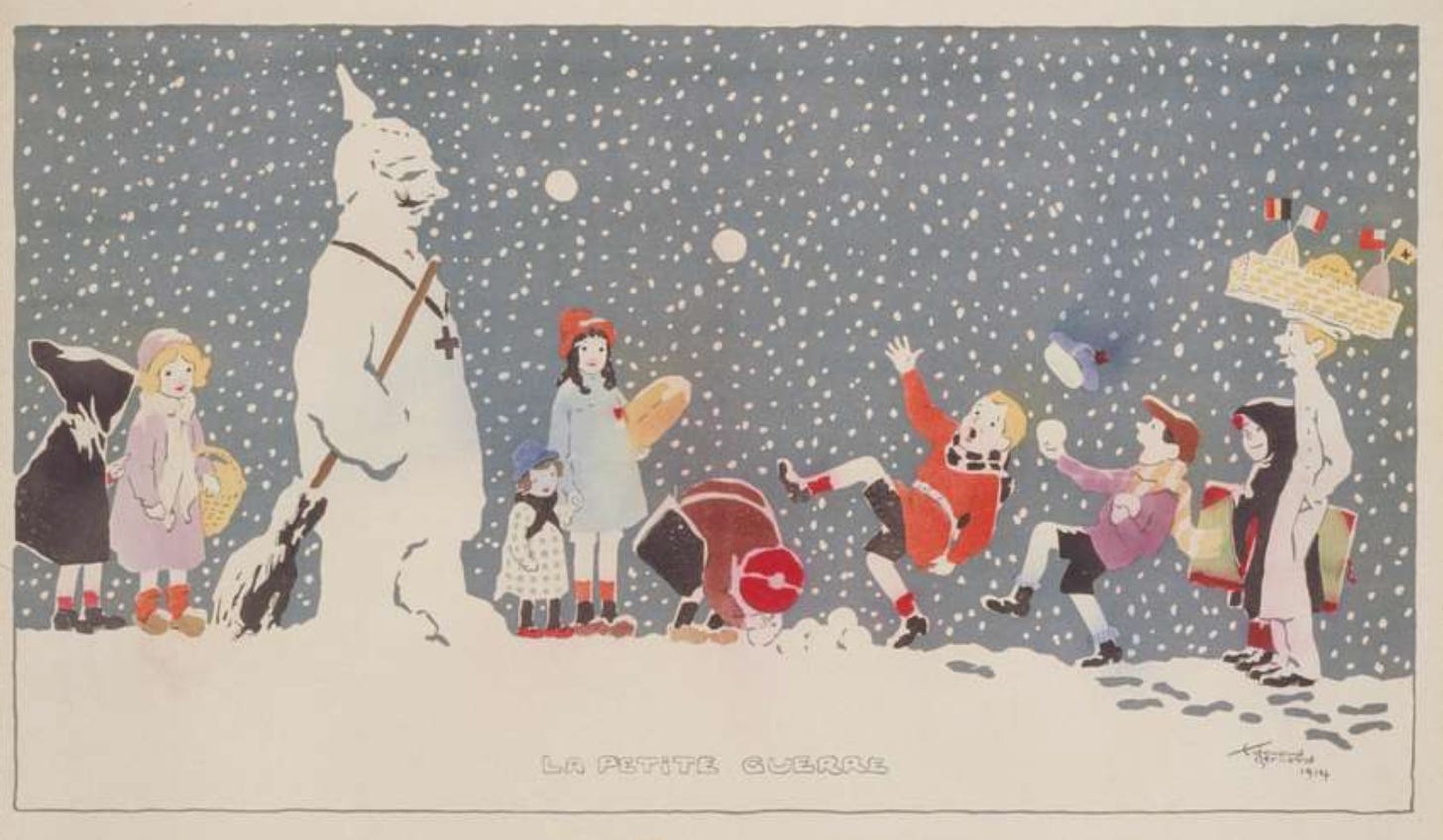

In the same period, snowmen were used to visualize the Kaiser in a form children could attack.

In this brief history, snowmen have been used as a means of creating beautiful public art and as symbols of antisemitism, protest, innocence, and war.

This likely flies in the face of how we imagine snowmen. I know my own image of them was shaped by the sweet “Frosty the Snowman” song from 1950 and the animated movie. Less sweet, and frankly puzzling was the 1998 Christmas bomb, Jack Frost, starring Michael Keaton as a dad who ignores his family to pursue his music career, only to die in a car accident and revisit his son when he is brought to life as a snowman. How? You might ask, presuming you’re willing to come this far in the logic-free zone that is every Christmas movie. He is awakened as a snowman when his son plays a magical harmonica that he gifted his son not long before his death. (“Makes cents!” - hopeful studio exec who greenlit this.) I am still traumatized by the CGI face of this snowman who was designed to look like George Clooney, who was originally attached to star and wisely said “I’m too hot to be a disturbing CGI snowman.”

My only other point of reference growing up was this Campbell’s soup ad from 1993 that for some reason lives in my head rent-free. A snowman comes inside from the cold and is handed a bowl of soup by some female-appearing hands (presumably mom). Slowly, he melts all over perfectly nice wood floors, and is revealed to be a boy. “Never underestimate the power of soup,” Campbell’s warned, setting me up for a lifetime of disappointment for the limits of soup.

But in this varied and mystifying use of snowmen, I still keep returning to the meaning of Hot Frosty. What can we make of this snowman and what does it say about us?

While I agree generally that the rise of Christmas movies that are light on plot and big on feels is likely a reflection of women’s desire for a harmless and feel-good escape from what experts are calling “life in 2024,” I think it’s more than that.

Not to get too into the plot of Hot Frosty, which is basically an insult to the concept of plot, but Lacey Chabert, playing a grieving widow, brings the hot snowman to life by draping a red scarf on him, taking a pic, and walking away. He is standing amidst some amateur-looking snowmen (no shade), the only one seemingly inspired by Renaissance traditions of “this could be marble but I’m balling on a budget” public art focusing on muscle-sculpted men. Once awake or. . . alive? (not my area), he discovers he’s naked (giving Garden of Eden), and then takes clothes from a thrift store after locals think he's a streaker. In all of this, we are meant to believe he’s like an air-gap computer of a person who has no knowledge of what it means to be hot (and why women stare at him), but does understand cancer as the thing that killed Lacey’s husband. I don’t want to admit how much I’ve considered the mental map of this snowman, but here we are.

I note this not because this is clearly in the tradition of Elf and other movies that present manchildren as romantic leads for women to love as innocents who present romantic fulfillment without the threat of misogyny. For me, Hot Frosty is more than a story about a hot man. It’s a story about the fantasy of women controlling men’s bodies. He helps restore Lacey’s house (and heart), and helps women all over town, seemingly oblivious to the ways they ogle him. We are meant to believe he doesn’t know what conventional attractiveness is or that he has it. He also doesn’t get that he’s white, but in the proud tradition of these kinds of movies, race is not something anyone in these worlds can see.

Though he seems to understand that he needs to stay cool (real cool in West Side Story terms), Lacey is the one who has to tell him when he’s getting too hot and needs to go outside to literally stay alive. I could ask why he isn't fully sleeping outside, but then again, logic has no place here. The point is that she is the one in control. She keeps him safe. At the end of the movie when he’s in a jail cell (don’t ask), it is Lacey who notes the cruelty of the state’s control of his body (keeping him in a hot jail cell) which can literally threaten his health. (As I say of my house plants, “he can’t thrive if he’s not alive.”)

In the leadup to the election, neo-nazi Nick Fuentes posted “your body, my choice” and that refrain has since been used as a form of abuse against women whether online, in the halls of high schools, or elsewhere. This provocation overtly claims the control of women’s bodies for men. Even typing this, I find the prospect of this worldview and its spread terrifying for every woman who has bled out in hospital parking lots knowing they wouldn’t receive necessary care inside, or questioned the trajectory of her reproductive life if it meant subjecting herself and her health to the decision making power of others.

Now, I get how crazy it is to invoke this in a conversation that began with a movie featuring a hot snowman, especially from a queer woman. However, I think if we want to understand the appeals of these kinds of movies we need to think about just what fantasies they offer and just what kinds of things inspired the need for such pop culture escapes now.

If men today were perceived as emotionally aware beings, we would not need to bring a snowman to life to date Lacey Chabert. If women felt their own autonomy over their bodies was assured, we wouldn’t need a movie where Lacey gets to play at “protecting” the body of a vulnerable man who seems desexualized to the point of Ken doll territory. He doesn’t understand the threat his attractiveness poses to him, so thank God Lacey is there to protect him! He lives on ice cubes but doesn’t understand what makes snow melt, so thank God Lacey can push him outside to keep him alive!

While many have pointed to this and other films in this vein as evidence of women wanting the fantasy of men who care for them without extracting labor, emotional or otherwise, I think we miss something here about power. These movies take women seriously (even if they are lawyers returning to their small towns to save the family’s pumpkin patch, or insert a similar plot here). Like someone making a snowman, this is a genre that lets women reshape imaginary worlds as they want them to be, sometimes in their own image. Hot Frosty is, after all, a nurturing caretaker who is selfless to the point of self-destruction. Sounds very traditionally female-coded to me.

In these movies, women don’t have to fear threats of violence or a lack of control over their right to make decisions about their lives or bodies. It’s interesting that many of the plots, for example, hinge on a woman making a choice to change her own life (I will move home and take over the family pumpkin patch!) or to fall in love with a snowman turned. . . man? The Campbell’s soup ad was wrong. We don’t need to remember the power of soup, we need to remember the power of women. After all, it’s mom and her soup making skills that turn the snowman into a boy. It’s Lacey Chabert who turns a snowman real, and women who transform Hot Frosty into a hit on Netflix.

Call Me! (or not!)

I’d love to hear from you! Drop your thoughts in the comments to share with the Landline community, or reply to this email to contact me. You can also find me on Instagram, or email me. I don’t have a dedicated phone line yet (just like in my youth), but maybe someday I’ll achieve Claudia status and get a Landline.

Thanks for reading!

This is a free post for subscribers of Landline. Consider subscribing to the paid plan to get my weekly email of recommendations and links, a podcast episode, and more! You can also help me spread the word by sharing it with a friend who would love it. Thank you for being a friend!

Thank you for this thoughtful jaunt through the snow, and for saving me from having to figure out for myself wtf the deal with Hot Frosty is. ☃️